Don't have an account?

Register NowYou have to add to cart at least 5 bottles or any program to make checkout.

- BlogThe History Of Peyote

The History Of Peyote

Published: February 22nd, 2017

Categories:

Plants and Seeds

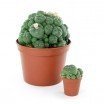

The woolly Mexican cactus Lophophora williamsii – also known as Peyote - has provoked controversy ever since Europeans arrived in the New World. Known for its “satanic trickery” by Spanish conquistadors and still attacked by governments and religious groups, the plant has nevertheless continued to play a large role in the religious and sacramental rites of native peoples, particularly in Mexico, but also among Native American tribes.

PRE-EUROPEAN USE OF PEYOTE

Archaeologists have found evidence of the plant in graves and in cave art that dates back to 4,000 B.C. The earliest European records mentioning the sacred cactus were written in 1499. As Juan Cardenas, whose insights of the Indies were published in 1591 wrote, “There was another herb … called peyotl. It is white. It is found in the North Country. Those who eat or drink it see visions either frightful or laughable. This intoxication lasts two or three days and then ceases. It is common food of the Chichimeca, for it sustains them and gives them courage to fight and not feel fear nor hunger nor thirst. And they say it protects them from all danger”.

It is unlikely, however, that the Chichimeca were the first Indian tribe to use peyote for spiritual and other purposes and its use was widespread by the time of the Spanish Inquisition. Spanish explorers in Mexico, including several 17th century Jesuit priests wrote and testified to the fact, that Mexican Indians used the drug for many purposes – ranging from spiritual to medicinal. It was of such interest to the Spaniards, despite early missionary disapproval, that it was even sent to King Phillip II of Spain’s personal physician to study for its medicinal qualities.

Most missionaries, however, opposed its use, particularly because it interfered with their conversion of local peoples to another religion – Christianity – in which the drug was forbidden. In fact, the use of peyote began to be suppressed in part to convert the native tribes.

Peyote has many different names in native tongues. Known as “seni” to the Kiowa, “wokoni” to the Comanche, “ho” to the Mescalero and as “hikori” to the Tarahumara, the plant was originally used by the Carrizo, Lipan, Apache, Mescalero, Tonkawa, the Karankawa and the Caddo tribes.

The plant was also a common item used in trade between tribes, both who lived in the area where the plant grows naturally, and far further north – which is how knowledge and use of the plant spread north from Mexico.

THE OKLAHOMA PERIOD

After peyotism reached Oklahoma, the rituals, at least among native peoples, began a significant transformation from earlier peyote ceremonies. Ritual gatherings began to become more family gatherings than hedonistic celebrations. After 1880, in fact, peyotism spread rapidly, despite the objections of missionaries and agents of the U.S. government who sought to suppress it. The Comanches and Kiowas reportedly traveled from as far away as Oklahoma to harvest peyote for ceremonial use after Oklahoma became designated “Indian Territory” in the 1880’s.

These trips are also of a highly spiritual and ritual nature. Pilgrims carry tobacco gourds to transport water and take only tortillas with them for nourishment. Today, of course, much of the trek is accomplished by car, but up until the middle of the last century, Indians still walked over two hundred miles to obtain the same, particularly after the establishment of the Native American Church.

The efforts to practice religious ceremonies, that involved the cactus eventually led to the more widespread protection of individuals who use the substance as part of religious ceremonies and rituals, but there are to this day isolated incidents where users are prosecuted for possession, particularly in the Deep South.

WHAT IS BEHIND THE FUSS?

Peyote contains a psychoactive alkaloid called mescaline. It can cause a wide range of effects, including deep spiritual insight and auditory and visual hallucinations. The bitterness of the plant often causes the user to feel nauseous prior to the psychoactive trip. Common use of peyote, or mescaline as it is also referred to, is by chewing the cactus or boiling it to create a reduction, that can be consumed as tea.

Long-term use of Peyote has not been found to cause any serious side effects, although as of today no academic studies have ever been performed to narrow down either the exact effects of the plant or the impact of longer term use. It is not thought to be addictive. That said, sustained use of the drug can also lead to poor eating habits, interrupted sleep patterns and other behaviors that might interfere with day to day activities.

For all the controversy however, peyote is a rather non-assuming, squat, spineless cactus that may be blue, green, yellow, green and red with yellowish or whitish hairs. Adult cacti measure between 4-11 centimeters in diameter and grow to a height of at most 11 centimeters. It grows in an area that stretches from the Chihuahuan Desert to the South Texas Plains on either side of the Rio Grande River. Each of the Peyote cactus disc-shaped “buttons” connects in the center of the plant that looks kind of like a rose.

MEDICAL APPLICATIONS OF PEYOTE USE

The drug has long been used medicinally in native Indian herbal practices. Taken in small doses, peyote is a mild stimulant and reduces appetite. The plant contains peyocactin, a water-soluble, crystalline substance, that possesses antiseptic and antibiotic properties against many different types of bacteria. Peyote also contains hordenine, which inhibits the growth of several different strains of Staphylococcus bacteria, that are known to be resistant to penicillin.

Natives also applied masticated peyote to burns, bites, wounds and aching muscles. The Tarahumara Indians also chewed pieces of the cactus during epic, long distance foot races, that often exceeded 50 miles. Kiowas used the plant to treat flu, scarlet fever, tuberculosis and venereal disease. Indian tribes also used the plant to reduce pains experienced during childbirth, toothache and associated with certain kinds of skin disease.